Using Python and Keras on the Kaggle Titanic Data Set

Surviving The Titanic

Introduction

I clearly remember visiting the Molly Brown House when I was an elementary school student growing up in Denver. Molly Brown was a socialite and philanthropist that lived in Denver around the turn of the century. Despite her many generous contributions to society, she is probably best known for being one of the survivors of the sinking of the RMS Titanic. Check out the Denver Historical Society’s web site for more about The Unsinkable Molly Brown.

At this point, you may be wondering what all this has to do with data science. It is not all that surprising that Molly Brown survived the sinking of the Titanic when you compare her to other passengers that survived. Molly was a first class passenger and female. Those two facts weighted greatly in her favor, as we will soon see.

Kaggle

Kaggle.com is a great resource for people interested in learning and working with topics in Data Science. In addition to hosting various competitions regarding data prediction, Kaggle also hosts an ongoing introductory competition based on passenger data from the Titanic’s last voyage. The data for this blog post comes from that introductory competition.

Who Survived and Who Perished

The story of what happened that night is well known. Kaggle sums it up this way:

The sinking of the RMS Titanic is one of the most infamous shipwrecks in history. On April 15, 1912, during her maiden voyage, the Titanic sank after colliding with an iceberg, killing 1502 out of 2224 passengers and crew. This sensational tragedy shocked the international community and led to better safety regulations for ships.

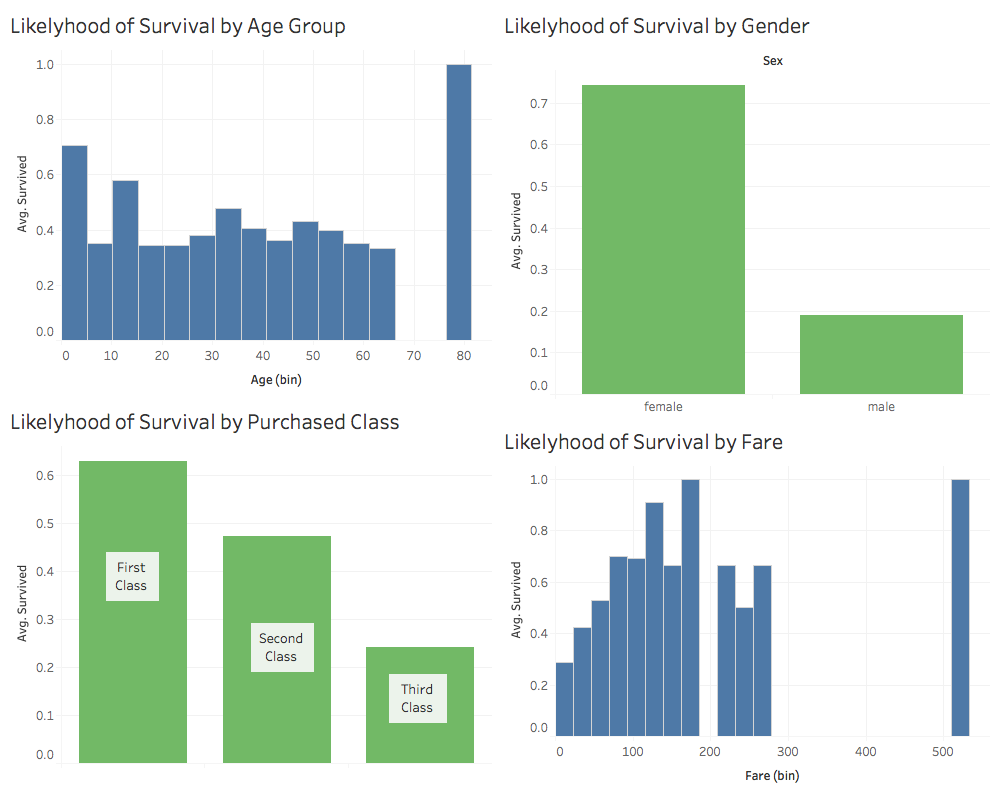

So, just who survived and who didn’t? In looking at the data, we can see some interesting patterns. The following are a few simple graphs that I developed using Tableau (a commonly used data analytics tool).

The first 4 graphs above show information regarding survival based on the age, gender, class and fare paid for the journey. From these graphs, we can see that:

- Infants and children ages 0-1 as a group had a much higher survival rate than older passengers. (Except the on 80 year old passenger that did survive.)

- Women as a group were far more likely to survive than men.

- People in first class had the highest survival rate as a group vs. those in second or third class.

- The more that someone paid for their fare, generally the more likely they were to survive.

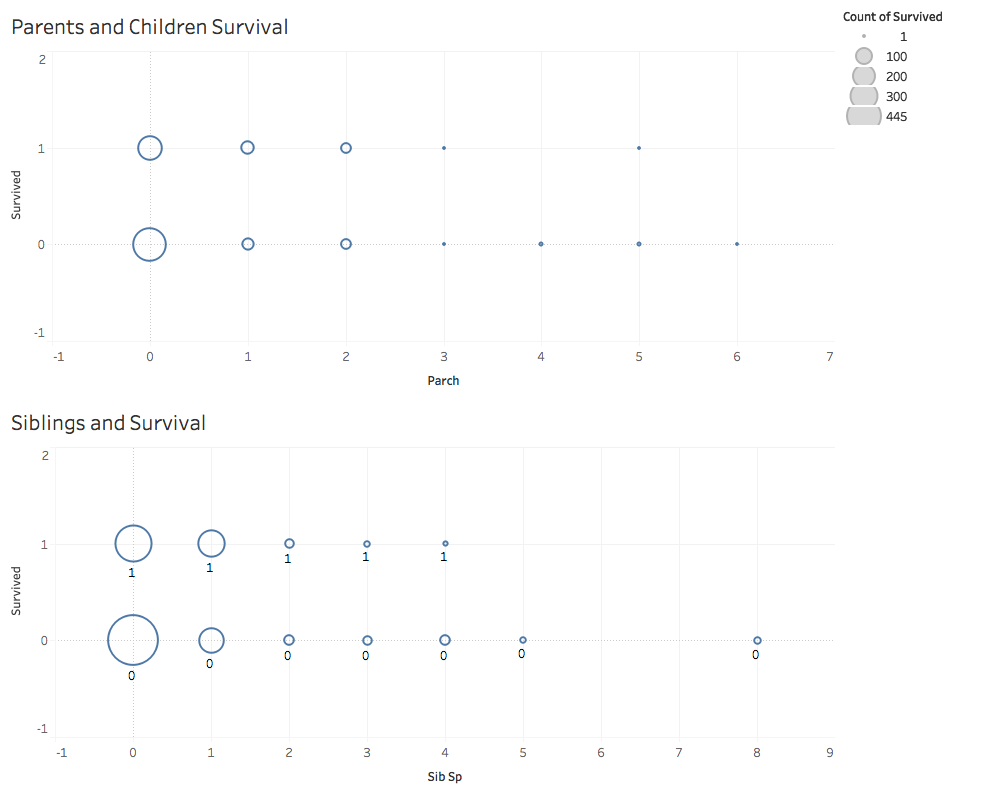

The last two charts show how the survival of the passengers breaks down based on a passenger’s parents/children and the number of siblings on board. In the last two charts, a survival of 0 means the passenger perished, and 1 means that they survived. The size of the bubble indicates the relative number of people in that group. For instance, people with no siblings where more likely to perish than survive. However, for instances where there was 1 sibling on board, slightly more survived (112) than didn’t (97).

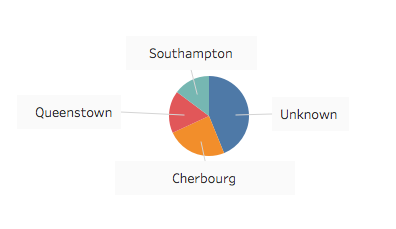

The following pie chart shows people that survived based on where they got on the ship.

The data points to the fact that where people got on the ship, had an impact on their survival. People that boarded the ship at Cherbourg were more likely to survive than the other ports of call. Note that the town of “ Queenstown” was renamed in 1920 to Cobh. If you’re curious, Jack and Rose (from the movie) boarded in Southhampton.

Side note: While there may have been some social biases that affected who survived and who didn’t, it is important to keep in mind how disorganized the evacuation efforts were on that tragic night. The ship sank quickly, and there were not enough life boats. Not all passengers had access to the ones that were there (most notably passengers in 3rd class). Many of the lifeboats that did launch were not anywhere close to full. Molly Brown’s boat, for instance, could have held 65 passengers and crew. Unfortunately, it only had 22 people on board.

The Problem

There are a number of different ways to tackle the problem of building a model that predicts who would survive the disaster and who wouldn’t based on the combined data above. In the end, what we are looking for is a model that takes in several components, and outputs either a 1 or a 0 to indicate survival or death.

An Approach

In designing a solution to this problem I opted to go with a neural network that would predict survival based on age, gender, class (first, second or third), fare paid, and point of embarkation. In looking at the other parameters, it was hard to tell if there were sufficient enough data to impact the outcome. It seemed to me that a person’s age and gender would be immediately obvious during the disaster. The fact that the person had paid a high fare, or were in an upper class seemed to me to indicate that they might be located in the upper decks at the time of the disaster and would have been able to get aboard a lifeboat. Lastly, if the people got on at Queenstown, they most likely would have been Irish. I have a feeling that the Irish didn’t fare to well in the disaster.

Looking at the specific input parameters for the network.

While it is true that the Keras toolkit that I used could have successfully scaled the input and output parameters, I decided to massage the data a little bit before training my neural network.

- Class: The passengers were either in first, second or third class. I decided to flip these numbers around and scale them from 1 to 0. I did this because I felt that it would match better with the fact that the network would ultimately output 1 for survival and 0 for death. So, first class = 1, second class = .66 and third class = .33

- Gender: For this parameter, I went with a 0 for male, and a 1 for female. I chose this based on the same logic as above. If a passenger was female, they were more likely to survive.

- Age: For age, I scaled the data between 0 and 1 by finding the maximum age in the data and then dividing each record’s age by that number.

- Fare: I used the same approach here that I did to age. I simply scaled the data between 0 and 1.

- Embarkation: Here I used a 1 for passengers from Southhampton, .5 for Cherbourg and a 0 for Queenstown based again, on the fact that those were the most to least likely to be associated with survival.

The overall network structure.

The following code shows the network structure that I used on this problem.

...

inputs = Input(shape=(5,))

x = Dense(150, activation=K.softmax)(inputs)

x = Dense(150, activation=K.softmax)(x)

predictions = Dense(1, activation=K.sigmoid)(x)

model = Model(inputs=inputs, outputs=predictions)

model.summary()

model.compile(optimizer='rmsprop',

loss='mean_squared_error',

metrics=['accuracy'])

...

Results

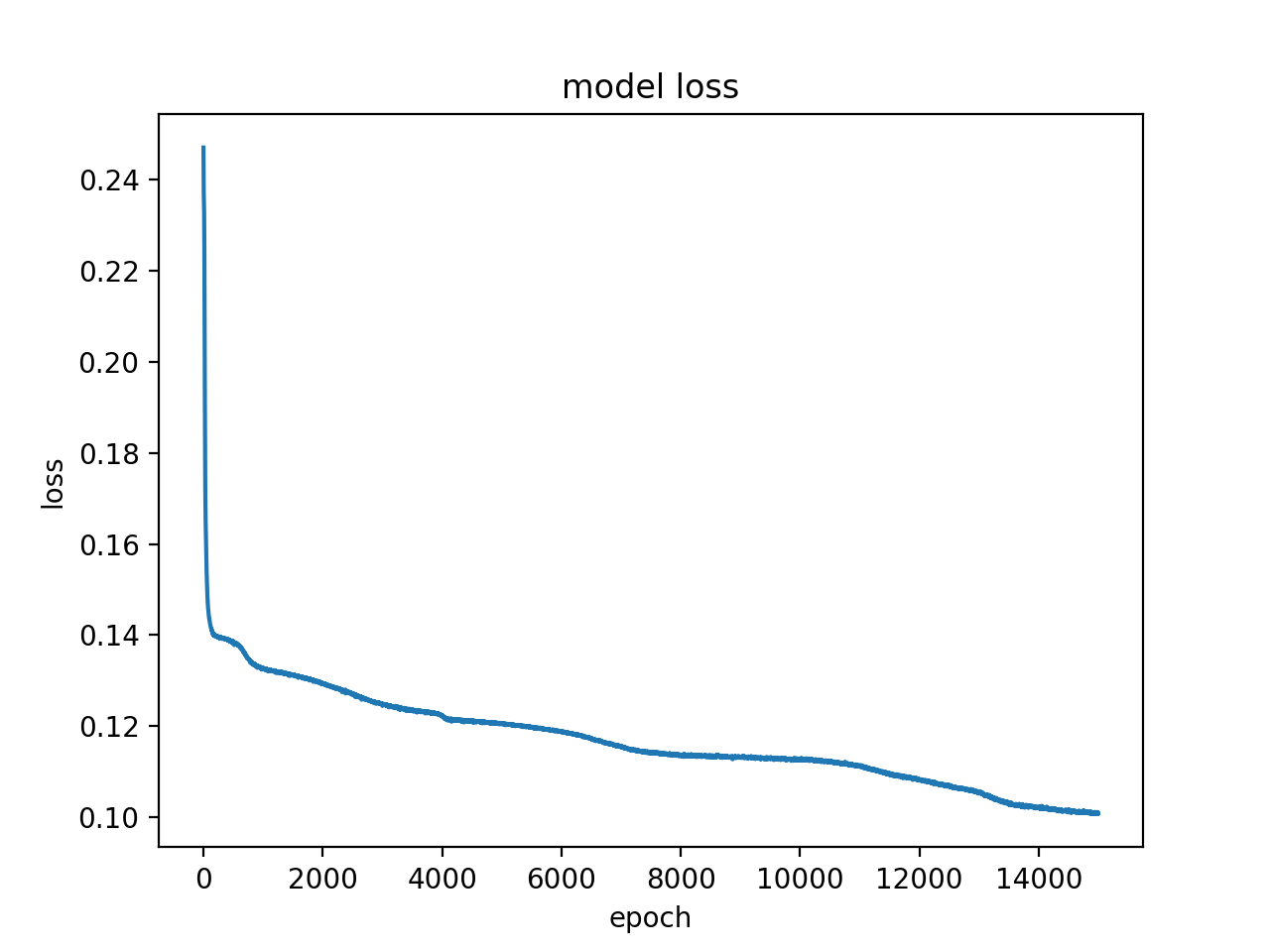

Here is the the learning curve for the network:

The results from the Kaggle competition was an accuracy of 73.684%. My score was 6381 out of 7121. That was not great, but considering it was my first attempt, I feel pretty good about it. In looking at the learning curve, it looks to me like the network was still learning when it switched over to predictions.

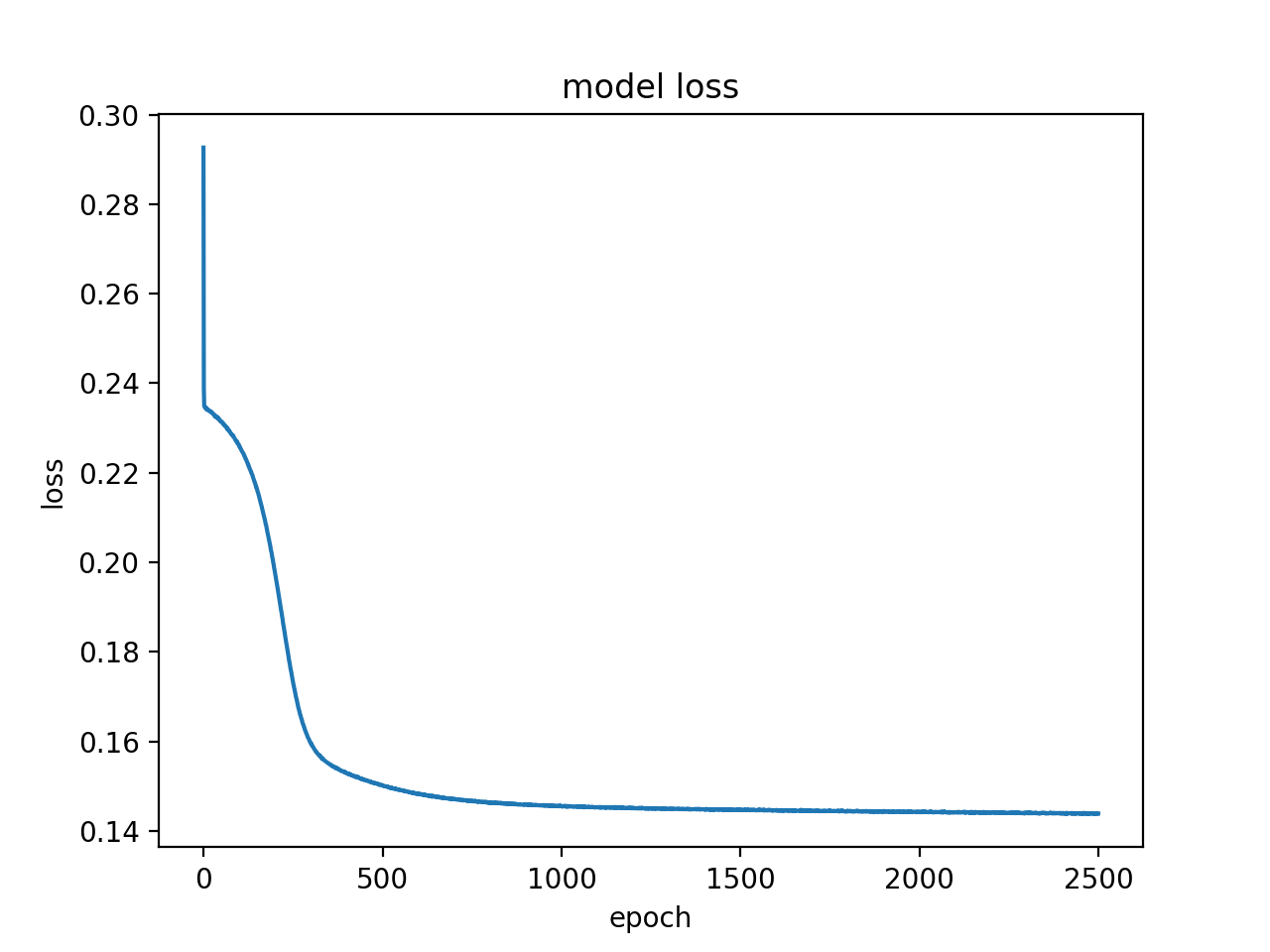

In a second attempt at training a net, I did a bit better. The second network had a few tweaks. First off, I used a 5 layer network with the three hidden layers having 100 nodes each. I also changed the network optimizer to be a stochastic gradient descent optimizer. I also modified the training to use a batch size of 25 and a total of 2500 epochs.

The results from this run was an accuracy of 76.555%.

Conclusion

Using neural networks is one possible way to tackle problems similar to the Titanic prediction problem posted by Kaggle. Another possible approach might be to try some kind of cluster analysis of the people who survived and who didn’t. It might also be interesting to predict the survival of passengers based on their closest match to people from the training set. While I didn’t really think that I was going to win the contest, I did enjoy the exercise. I will definitely keep my eye out for other Kaggle challenges, and will possibly join a team in the future.

It is hard not to work on this data set without giving some thought to the people that perished. One thing that did lift my spirits, was learning more about Molly Brown. After the Titanic sank and the survivors were aboard the Carpathia, Molly went to work. By the time they reached New York, she had raised over $10,000 from wealthy passengers to help those who were financially decimated by the sinking of the Titanic.

The code associated with this post can be found on github:

https://github.com/fractalbass/titanic

Thanks for reading! I’ll be back soon with more blog posts on the topic of data science.

Update:

I was curious how the neural network would compare to just trying to find the closest match to each record from the test set in the training set and then assigning the survival based on the training set. I think of it sort of like a closest buddy test… Or, more appropriately the closest known point in the 7-dimensional space defined by passenger class, age, number of siblings, number of parents or children, fare and embarkation point. It turns out that this method is not very good. I achieved only 56.938% accuracy using this method. When I normalized the fare and age data to range between 0 and 1, I was able to increase the accuracy to 57.416%.

This surprised me a bit. I would have thought that this brute-force method would have been more accurate. I guess there is something to this neural net stuff after all. :)