KMeans Clustering and Crime Data

The League of Justice

One of my favorite Saturday morning cartoons as a kid was “Super Friends”. This show featured Superman, Batman and Robin, Wonder Woman, Aquaman, Wendy, Marvin and Wonder Dog.

Later, Wendy, Marvin and Wonder Dog were replaced by “The Wonder Twins” Zan and Jayna and their pet monkey Gleek.

The show featured a powerful TroubAlert computer which was located in the Hall of Justice. The computer would alert the Super Friends in the event of criminal activity, environmental disaster, or other calamity. The Friends would then dash out and save the day.

What does this have to do with data science, you ask? Hang in there. You’ll see.

Clustering

Clustering is a useful tool frequently employed in data science. This technique allows us to group together similar objects based on their characteristics. A great introduction to this topic is given on datascience.com

For this exploration into clustering, I am going to take a look at some geolocation data. This is a bit different from some of the other clustering examples you may see on the net.

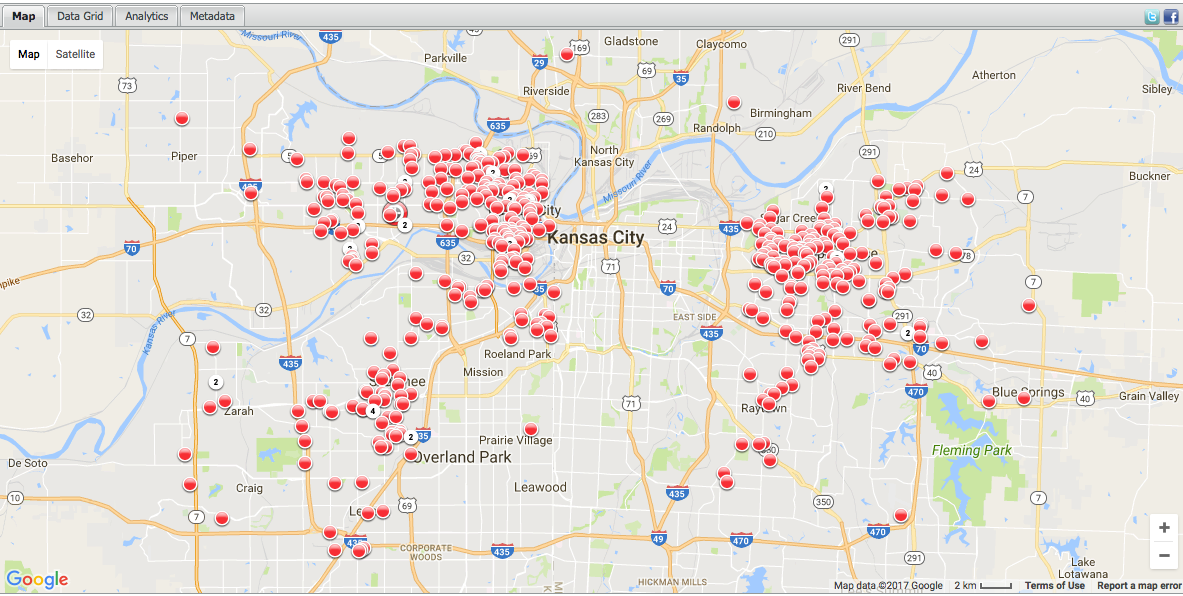

The first step in getting to a clustered solution is to determine a data set. The website communitycrimemap.com provides some nice maps that show crime data. For this example, we will look at Kansas City. We can use the above site to search for aggravated assaults from January 1 to June 22, 2017. Unfortunately, it turns out, there were over 500 instances of aggravated assault in that range!

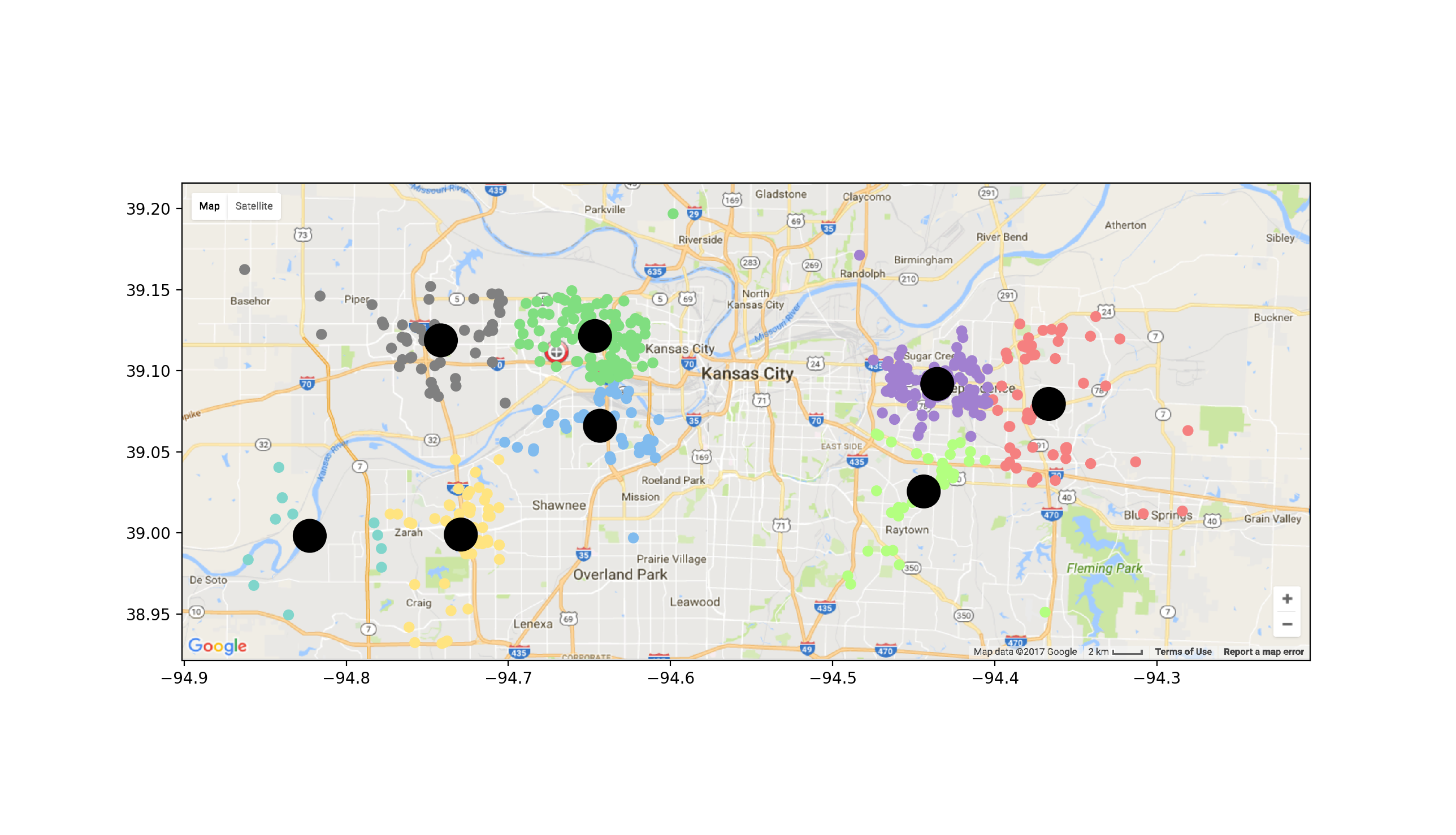

From the above graphical representation, we can start to see how the data is naturally clustered. However, what if we wanted to cluster this data into eight different subgroups? That will require some numerical tools as well as the raw data responsible for the above map.

In addition to analyzing data, data science also involves finding was to get access to data. We can leverage some of the tools for building dynamic websites and working with backend data APIs to tease the data out of this page.

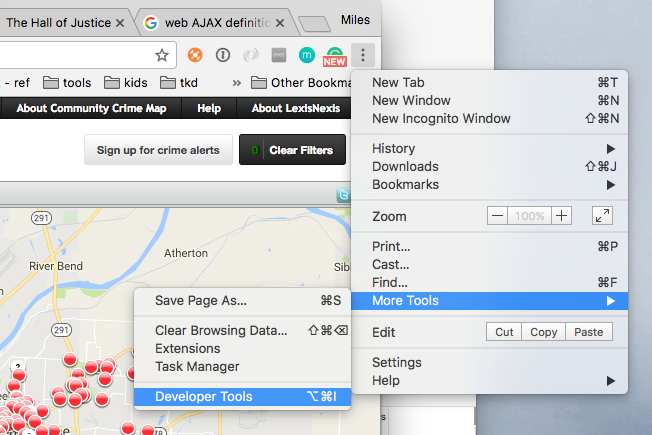

Chrome developer tools is a great resource for this type of task.

Chrome Developer Tools

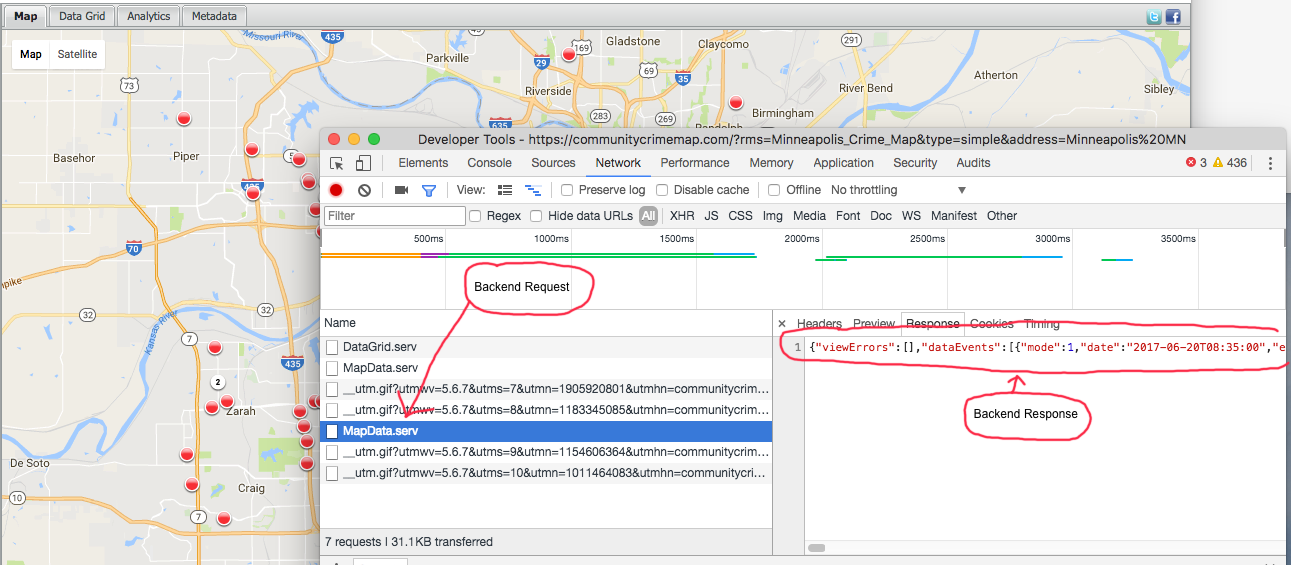

Chrome developer tools is built into the Google chrome web browser. The tool allows access to not only the underlying HTML that is used to render a web page, but also all of the AJAX (asynchronous JavaScript and XML) calls that are responsible for the dynamic data. The KC crime page does have an Ajax call behind the scenes. Using developer tools…

we can view the raw data behind the crime map.

From here, we can copy the data and paste it into a text file. (We could also write a python file that would pull this data directly from the website. In order to work with the data offline, I have decided to just put the data in a file.)

The results of the AJAX call are in JSON (Java Script Object Notation) format. Both “R” and Python have great tools for dealing with CSV files, however. To make things easier, we can write a Python program that creates a CSV file based on the contents of the JSON file. It is possible to use any number of programming languages to accomplish this task. We will go with Python here for the sake of consistency with the rest of this blog post.

A Word About Testing

Test Driven Development, or TDD, is a crucial part of modern professional software engineering. For an introduction to the topic, check out https://martinfowler.com/bliki/TestDrivenDevelopment.html as well as Kent Beck’s book on the topic.

It seems to me that TDD practices are particularly useful when dealing with data science. Unfortunately, I have yet to see a single test, let alone a project or example in “data science” that has been test driven. In this blog post, I will attempt to Test Drive what I am doing. It is the right thing to do, and the Super Friends would back me up on that.

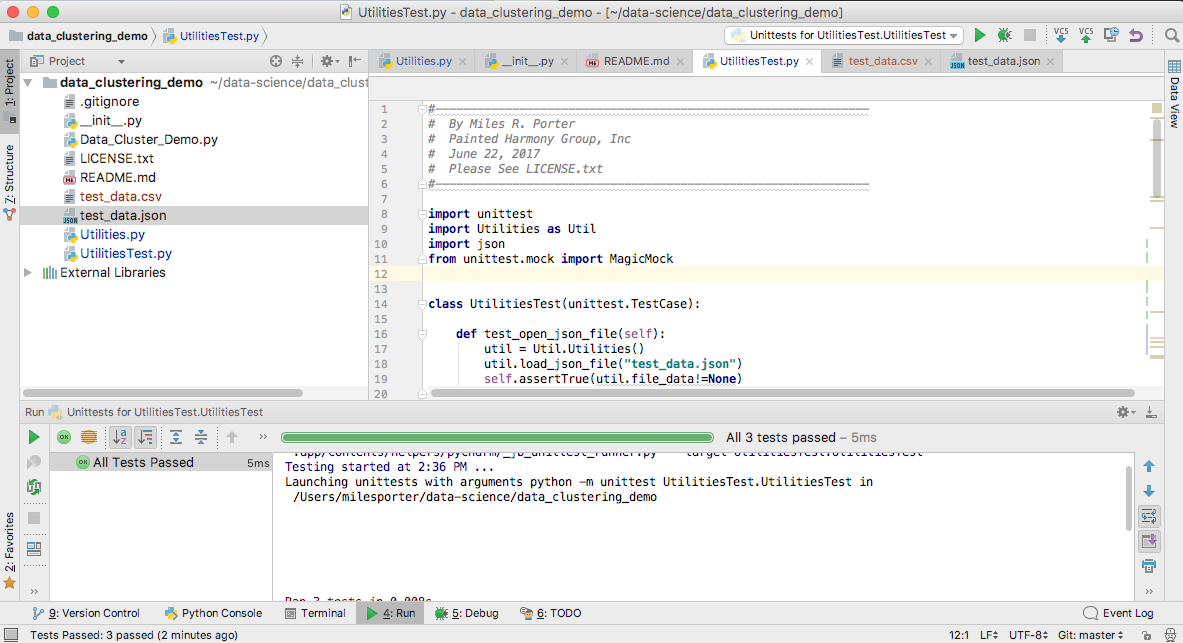

The Python feature for translating our JSON file to a CSV file will have three basic functions. To test drive this feature, we begin by writing tests for those functions first. Then we write code to satisfy the tests. Below you can see my three tests, plus one “integration” test at the bottom of the test class that confirms that the three parts work together:

#--------------------------------------------------------------

# By Miles R. Porter

# Painted Harmony Group, Inc

# June 22, 2017

# Please See LICENSE.txt

#--------------------------------------------------------------

import unittest

import Utilities as Util

import json

from unittest.mock import MagicMock

class UtilitiesTest(unittest.TestCase):

def test_open_json_file(self):

util = Util.Utilities()

util.load_json_file("test_data.json")

self.assertTrue(util.file_data!=None)

self.assertTrue(len(util.file_data["dataEvents"])==3)

def test_parse_lon_lat_data(self):

util = Util.Utilities()

util.load_json_file("test_data.json")

parsed_data = util.parse_lat_lon_data()

self.assertTrue(len(parsed_data)==3)

self.assertTrue(parsed_data[0][0] == 39.087646484375)

self.assertTrue(parsed_data[0][1] == -94.4664535522461)

self.assertTrue(parsed_data[1][0] == 39.10447311401367)

self.assertTrue(parsed_data[1][1] == -94.4247055053711)

self.assertTrue(parsed_data[2][0] == 39.11735916137695)

self.assertTrue(parsed_data[2][1] == -94.6497573852539)

def test_save_file(self):

# Read the file

util = Util.Utilities()

util.load_json_file("test_data.json")

# Parse the file

parsed_data = util.parse_lat_lon_data()

# Save the file

util.write_file(parsed_data,"test_data.csv")

# Check the file

with open("test_data.csv") as f:

content = f.readlines()

self.assertTrue(content[0].strip() == "lat,lon", msg="Error line 1.")

self.assertTrue(content[1].strip() == "39.087646484375,-94.4664535522461" , msg="Error line 2.")

self.assertTrue(content[2].strip() == "39.10447311401367,-94.4247055053711" , msg="Error line 3.")

self.assertTrue(content[3].strip() == "39.11735916137695,-94.6497573852539", msg="Error line 4.")

def test_all_in_one(self):

# Convert the JSON into a CSV file

util = Util.Utilities()

util.convert_json_file("test_data.json", "int_test_data.csv")

# Check the file

with open("int_test_data.csv") as f:

content = f.readlines()

self.assertTrue(content[0].strip() == "lat,lon", msg="Error line 1.")

self.assertTrue(content[1].strip() == "39.087646484375,-94.4664535522461", msg="Error line 2.")

self.assertTrue(content[2].strip() == "39.10447311401367,-94.4247055053711", msg="Error line 3.")

self.assertTrue(content[3].strip() == "39.11735916137695,-94.6497573852539", msg="Error line 4.")

Our tests will reference the sample JSON file below. This file is actually a portion of the file that we pulled down from the communitycrimemap.com site earlier. (Note: I have abbreviated the file below with ellipses to shorten it up a bit. The actual file used by the tests is longer.)

{

...

"dataEvents": [{

"latitude": 39.087646484375,

...

"longitude": -94.4664535522461

}, {

"latitude": 39.10447311401367,

...

"longitude": -94.4247055053711

}, {

"latitude": 39.11735916137695,

...

"longitude": -94.6497573852539

}]

}

We are now able to confirm that our Python class for reading, parsing and writing the CSV file works as expected. Here is the file that makes our tests pass.

import json

from pprint import pprint

import os

class Utilities:

file_data = None

def load_json_file(self, filename):

with open(filename) as data_file:

self.file_data = json.load(data_file)

def parse_lat_lon_data(self):

line_data = []

for event in self.file_data["dataEvents"]:

line_data.append([event["latitude"],event["longitude"]])

return line_data

def convert_json_file_to_csv(self, filename):

self.load_json_file(filename)

return self.parse_lat_lon_data()

def write_file(self, data, filename):

try:

os.remove(filename)

except OSError:

pass

f1 = open(filename, 'a')

f1.write("lat,lon\n")

for p in data:

f1.write("{0},{1}\n".format(p[0],p[1]))

For even more information on TDD, and why it is a valuable practice, check out this article: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ebfd/1d5422a12e8d2bbaae8392300dd4ed2d552e.pdf

Our tests confirm that the building blocks of our program that sets up the CSV file are working correctly. We are now ready to move on to manipulating our dataset.

A note about the development environment

One of the benefits of TDD is that it provides the developer a chance to debug small pieces of the code. Using an IDE that is suited for debugging can be very helpful. One such IDE is PyCharm CE. (PyCharm CE is a free, open source community edition IDE. There is also a PyCharm professional edition that is not free. Both are excellent tools for working with Python.)

https://www.jetbrains.com/pycharm/download/#section=mac

I have been using the PyCharm IDE on this small project for several reasons. First, as I just mentioned above, it provides a nice environment for debugging. It also provides tools for writing code, and working with GIT. The PyCharm IDE also supports numerous plugins and can be configured to work with different versions of Python.

Clustering

Now that we have the ability to convert the file into CSV format, we are ready to return to the main point of our exercise, which is to cluster the data.

Here is a program that does just that:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from Utilities import Utilities

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from pylab import *

import matplotlib.cm as cm

class DataClusterDemo:

def run(self):

# Create a CSV file that we can read into a dataframe.

util = Utilities()

util.convert_json_file("kc_aggravated_assault_2017.json", "kcav.csv")

kc_data = pd.read_csv("kcav.csv")

# Split the dataframe in lat and long series.

f1 = kc_data['lat'].values

f2 = kc_data['lon'].values

# Define the number of clusters we want

cluster_num = 8

# Discover the clusters

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=cluster_num).fit(kc_data)

cluster_labels = kmeans.fit_predict(kc_data)

centroids = kmeans.cluster_centers_

colors = 0.5 + (0.5*(cm.spectral(cluster_labels.astype(float) / cluster_num)))

# "Underlay the map below the points.

img = plt.imread("KC_Map.png")

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(img, extent=[-94.9013, -94.2054, 38.9214, 39.2158, ])

# Display the actual data points on the map. Note that our data is in the format of latitude, longitude.

# We need to plot these in reverse order to translate them to the X and Y axis.

plt.scatter(f2,f1, c=colors)

#Put a black circle in the middle of each cluster (a.k.a. centroid)

for c in centroids:

c = plt.Circle((c[1],c[0]),0.01, color='black')

ax.add_artist(c)

# Display everything. Because we are running this in pycharm, we set block to TRUE. This

# prevents the map window from closing right away.

plt.show(block=True)

dcd = DataClusterDemo()

dcd.run()

You may be wondering why this program does not appear to be test driven. I will admit that I am not completely comfortable with the fact that it isn’t. It is worth mentioning that this program uses several libraries (including numpy, pandas, sklearn and matplotlib) that are external to our project. Also, I am still trying to figure out how to best unit test some of the data-science related tools. Python does include MagicMock that can be used to “stub out” different parts of the system not under test. I will be looking more into that in the future.

The Important Part…

In the above program, the critical lines are…

...

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=cluster_num).fit(kc_data)

cluster_labels = kmeans.fit_predict(kc_data)

centroids = kmeans.cluster_centers_

...

These lines in the program use KMeans class from the sklearn.cluster module. This class does all of the heavy lifting for us. In the above, we first use KMeans to train a cluster based on the input data, and the number of clusters we want. We then use that model to get the cluster centers or centroids.

The program also draws a chart. This chart includes our data points and the cluster centers superimposed on top of a map of Kansas City.

# "Underlay the map below the points.

img = plt.imread("KC_Map.png")

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(img, extent=[-94.9013, -94.2054, 38.9214, 39.2158, ])

The final output of the program looks like this:

What value does this provide? Obviously, it answers the key question that you have been asking yourself for a while now…

How can we assign each of the 8 original Super Friends to a part of Kansas City in the best effort to fight crime?

Too much? Maybe.

Conclusion:

In this post we have demonstrated the following:

- Using google chrome developer tools to inspect dynamic web pages and extract data returned from backend APIs.

- Using test driven development (TDD) to create an application that can translate JSON files into CSV files

- Using pandas dataframes and sklearn Means classes and create a cluster analysis of data

- Using matplotlib to overlay clustered data analysis on top of a map (“png”) file.

- Finally, we made some crazy connections between “Super Friends” and data science.

There is much more to the process of cluster analysis than I have covered here. Be sure to check out the following resources:

- datascience.com tutorial

- https://home.deib.polimi.it/matteucc/Clustering/tutorial_html/kmeans.html

- https://www.dezyre.com/data-science-in-r-programming-tutorial/k-means-clustering-techniques-tutorial This one specifically covers K-Means clustering using “R”.

Complete code for this blog post can be found in the following GIT repo:

https://github.com/fractalbass/data_clustering_demo