Intro to R

Python is not the only language used in the field of data science. Another frequently used language is “R”. Before I dig deeper in the the Udacity course, I have decided to spend a little time exploring this language. As my guide, I will be using the Datacamp free tutorial on the language as well as looking at some data on my own. First, however, I need to get the thing installed. (The tutorial includes an online R interactive console. I prefer, however, to have the language installed on my mac as well.)

Installing R

Here are the steps I took to install R with homebrew on my Mac (running macOS Sierra Version 10.12.5).

brew tap homebrew\science brew install r

After the install was completed, I followed the instructions and ran the following script:

R CMD javareconf JAVA_CPPFLAGS="-I/System/Library/Frameworks/JavaVM.framework/Headers -I$(/usr/libexec/java_home | grep -o '.*jdk')"

Lastly, I followed instructions on this post to set up an R gui:

brew install r-gui brew linkapps r-gui

(Note: I found that the r-gui is somewhat unstable on my mac. After several crashes, I have opted to work with “R” from a terminal window. This seems much more stable.)

This created an app in the applications folder for the R console. Lastly, I created a shortcut in the doc bar to launch “R”.

Before I start exploring data on my own, it makes sense to review some of the basics of R and R data types.

Basic R Data Types

Variables

R has a similar hierarchy of data types as Python pandas. These types include variables, vectors, and data frames.

To assign a value to a variable we use the “<-“ notation.

> some_variable <- 100 > some_variable [1] 100

Note: you can display the contents of a variable by just entering the name in a prompt.

Vectors

To create a vector, we use a similar syntax combined with the “c()” function. This function is named “c()” because it combines values.

> some_vector <- c(10,20,30,0,-10) > some_vector [1] 10 20 30 0 -10

It is possible, with R, to name the elements in a vector. This makes it easier to reference the data rather than just referring to the column index (which is also possible.)

> names(some_vector) <- c("Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday", "Thursday", "Friday")

> some_vector

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday

10 20 30 0 -10

>

>

An interesting aspect to vectors is that they are indexed with the first element being 1. For example:

> some_vector <- c(10,20,30,0,-10)

> names(some_vector) <- c("Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday", "Thursday", "Friday")

> some_vector

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday

10 20 30 0 -10

>

> some_vector[3]

Wednesday

30

Matrices

R also has the concept of matrices. As you might expect, these are two dimensional arrays of the same data type. To define a matrix, you can use the following notation:

> mymatrix <- matrix(1:9, byrow = TRUE, nrow=3)

> mymatrix

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 1 2 3

[2,] 4 5 6

[3,] 7 8 9

>

R Data Frame Basics

An R data frame…

is used for storing data tables. It is a list of vectors of equal length.

http://www.r-tutor.com/r-introduction/data-frame

The following GIT repo contains the results of a survey on people’s opinions about the San Andreas Fault https://github.com/fivethirtyeight/data/tree/master/san-andreas. The data from this set can be used to explore some of the features of R data frames.

Loading Data

R has built-in features that make it easy to load data from files. The following shows how to load data into a data frame from a “.csv” file.

> setwd("/Users/milesporter/data-science/data-sets/san-andreas")

> mydata = read.csv("earthquake_data.csv")

This creates a data frame object that we can then use to analyze the data in the CSV file.

Once we load the data into a data frame, we can see what the columns are by using the “colnames” function like so:

> colnames(mydata) [1] "In.general..how.worried.are.you.about.earthquakes." [2] "How.worried.are.you.about.the.Big.One..a.massive..catastrophic.earthquake." [3] "Do.you.think.the..Big.One..will.occur.in.your.lifetime." [4] "Have.you.ever.experienced.an.earthquake." [5] "Have.you.or.anyone.in.your.household.taken.any.precautions.for.an.earthquake..packed.an.earthquake.survival.kit..prepared.an.evacuation.plan..etc..." [6] "How.familiar.are.you.with.the.San.Andreas.Fault.line." [7] "How.familiar.are.you.with.the.Yellowstone.Supervolcano." [8] "Age" [9] "What.is.your.gender." [10] "How.much.total.combined.money.did.all.members.of.your.HOUSEHOLD.earn.last.year." [11] "US.Region"

To view a specific column of data, we can address it by name or column number. For example

mydata$Age

(Note: There are several ways to accomplish this using slightly different syntax including mydata(Age) mydata[“Age”], mydata[[“Age”]], and mydata[8].)

This will return all of the items in the “Age” column. The result is returned as a vector.

> mydata$Age [1] 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 [10] 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 [19] 30 - 44 30 - 44 18 - 29 30 - 44 18 - 29 18 - 29 30 - 44 18 - 29 30 - 44 [28] 30 - 44 30 - 44 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 30 - 44 18 - 29 30 - 44 18 - 29 [37] 18 - 29 18 - 29 18 - 29 30 - 44 30 - 44 18 - 29 45 - 59 45 - 59 18 - 29 ... ... [1009] 60 60 30 - 44 30 - 44 Levels: 18 - 29 30 - 44 45 - 59 60

At first, it appears that when we reference a set of data in the data frame, it displays that data in a format that saves space. While this is true, it turns out that there is more going on. R will attempt to simplify an object if it can. When we reference mydata$Age, R recoginzes that this single column data frame could be cast as a vector. To avoid that we can do the following:

mydata["Age"] or > mydata[,"Age", drop=FALSE]

Both of these will display the data as follows:

> mydata[,"Age", drop=FALSE]

Age

1 18 - 29

2 18 - 29

3 18 - 29

4 18 - 29

5 18 - 29

...

1009 60

1010 60

1011 30 - 44

1012 30 - 44

1013

>

Some Basic Statistics With R

Now that we have the data, let’s do some basic statistical analysis. We will start with a simple frequency distribution of the age in the dataset. (Note: This data set contains survey information about earth quakes. Rows in the data set contain individual responses, and the ages column contains data in age “buckets”.)

> library(MASS)

> age = mydata$Age

> age.freq = table(age)

> age.freq

age

18 - 29 30 - 44 45 - 59 60

12 215 257 275 254

I find this display to be somewhat hard to read, but we can re-format the data using the cbind function like so:

> cbind(age.freq)

age.freq

12

18 - 29 215

30 - 44 257

45 - 59 275

60 254

If I want to find out which bucket has the highest frequency, I can use the max function along with the which function like so:

> which(age.freq==max(age.freq))

45 - 59

4

The number “4” in the display is actually showing us which column (not 0 based) has the maximum. This is more obvious when you look at the results of the cbind function above. The column [45-59] is the 4th column in the list of columns for age.freq.

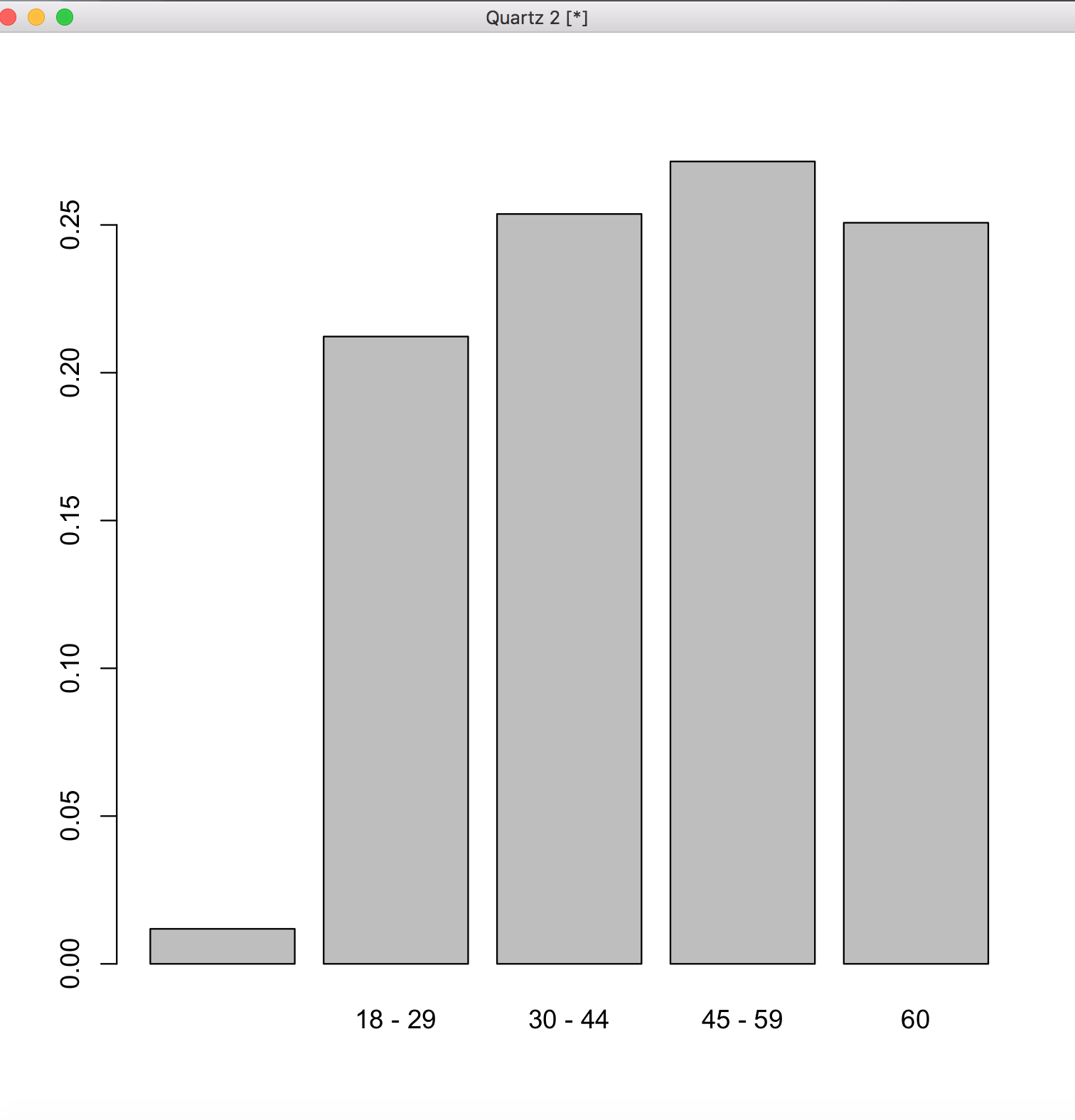

What if we want to find the relative distribution of the age of people that took the survey. We can do that as follows:

> age.relfreq = age.freq / nrow(mydata)

> cbind(age.relfreq)

age.relfreq

0.0118460

18 - 29 0.2122409

30 - 44 0.2537019

45 - 59 0.2714709

60 0.2507404

As a sanity check, we can verify that the relative frequencies sum up to one easily:

sum(age.relfreq)

We can also graph this distribution as so:

> barplot(age.relfreq)

Summary

This post has covered only the most basic aspects of R. Check out my next post as I explore more of the features of this language, and more topics in data science in general.